Figure 1: At 27, I have worries I can’t tell anyone.

Introduction: The Problem with the “AI Replaces Experts” Narrative

In recent years, we hear everywhere that specialized white-collar jobs will be taken by AI.

I’ve been deeply immersed in Data Science (DS) since my undergrad—through work, research, and hobbies. Lately, tech-illiterate family members and friends with no programming experience have started asking me (without any malice), “Are you still doing programming?” or “Can’t AI do everything now?”

These voices aren’t just coming from family. Surprisingly, even elite managers at famous corporations and long-time consultants have told me:

“I wouldn’t recommend trying to make a career in the DS field.”

“Aren’t data scientists going to be the very first profession replaced by AI?”

Figure 2: Is that really true?

Just the other day, a brilliant grad student I know was seriously considering dropping out because he was misled by people around him saying “the future of data scientists is dark.”

I believe the probability of data scientists’ jobs being completely replaced by AI within a few years is extremely low. I feel a strong sense of crisis about the current situation where excessive expectations for AI lead to poor corporate decisions, and extreme views like “AI will do everything, so I don’t need to learn anything anymore” are spreading.

As someone on the data analysis side, I feel a responsibility to state my position clearly. I’ll represent 1 the people in the field and provide an “answer” to each of these common claims:

Figure 3: I’m not a rapper

Current Challenges of LLMs

“AI can write code, so data scientists will become unnecessary.”

This is something I was actually told by a consultant active on the front lines.

Indeed, the changes brought by AI in the field of coding over the last few years have been staggering, and it’s no wonder people think that way. The AI Applicability scores calculated by Tomlinson et al. (2025) place “Data Scientist” in the top 30, showing a high affinity between DS tasks and generative AI. As I wrote in a past blog post, I’ve been using generative AI since late 2022 and benefit from it in coding, research, documentation, and studying.

However, the idea that “data scientists are unnecessary because of generative AI” is as off-target as saying the invention of the power saw makes carpenters unnecessary.

(Premise) “Data Scientist’s Job = Coding” is False

Generally, the job called “Data Scientist” includes a wide variety of roles. Therefore, even if LLMs replace coding tasks, the job of a data scientist doesn’t disappear. The realistic scenario is a shift where time spent writing code manually decreases, allowing more time for high-value tasks like problem definition, analysis design, supervising/verifying implementations, and communicating with stakeholders. (In fact, this change has already begun in many jobs.)

Limits and Risks of Coding with Generative AI

I also feel a gap in perception regarding the coding abilities of generative AI when talking to those who don’t code. Perhaps they think that by using tools like AI agents, anyone can easily perform advanced tasks, including data analysis.

However, letting AI handle coding has two sides that cannot be ignored: its “limits” in capability and the “risks” brought by the generated code.

Good at Simple Tasks, Bad at Complex Ones

Tasks like quick aggregations or plots—one-off code—are often handled well enough by AI. I’ve used tools like Claude Code or opencode to create simple tools in minutes without writing a single line myself.

But the reality is that it is nearly impossible to let AI handle multi-step tasks or code that needs long-term maintenance.

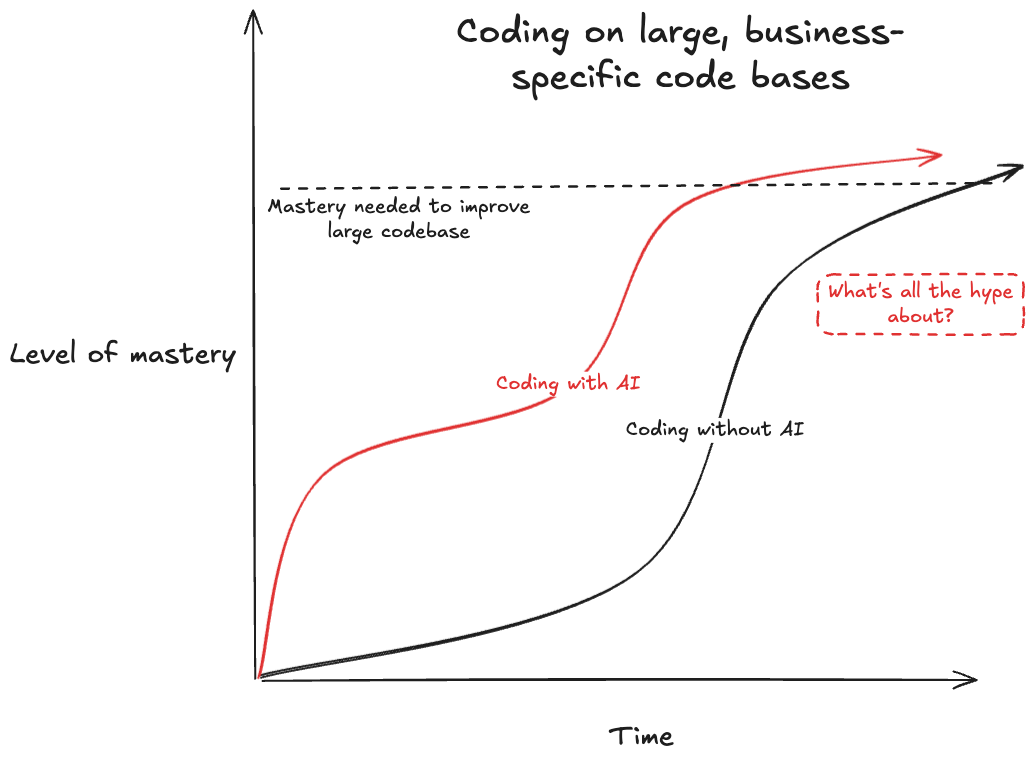

Figure 4: The time to master a large, complex codebase doesn’t change much with or without AI.

As METR research shows, AI might look like it performs excellently on coding benchmarks, but it falls far short of human performance in actual projects.

LLMs are often trained with RLVR (Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards), specializing them for “verifiable” tasks like tests, but making them weak on hard-to-verify aspects crucial in practice: documentation, code quality, readability, and maintainability.

Data analysis has poor compatibility with LLMs regarding verifiability. Unlike software UI/UX or APIs, data analysis has no “single correct answer,” making it hard to create tests based on “normal behavior.”

AI might generate plausible-looking graphs or statistics. But it is extremely bad at spotting signs of a “bad analysis”—like confounding factors, selection bias, or data leakage—and judging if a conclusion is valid in a business context. There is a huge gap between results “looking right” and “actually being reliable.”

Thus, to perform a valid analysis based on LLM code, thorough human review is ultimately necessary.

One might argue:

“Then just let AI do the review too.”

But mutual review between LLMs has problems. LLMs have limited self-correction abilities. One study showed that while 60% of human review comments led to code changes, LLM review comments only resulted in changes 0.9% to 19.2% of the time (Sun et al. 2025).

The critical issue is the context bottleneck. A good code review isn’t just a bug check. It requires understanding if the code fits the business goal and design philosophy. Since AI lacks this deep contextual understanding, it can only provide superficial reviews.

Unmaintainable Code and Security Risks

The side effects of LLMs in engineering are non-negligible. In agent-based editors like Cursor or Claude-Code, code is generated without much thought from the user. Humans naturally take the easy path. Code with unclear intent increases, and AI applies quick-fix patches for every error, eventually resulting in legacy code that looks like an illegally extended building. Such code is no longer an asset; it’s a liability.

Unmaintainable code is a serious security vulnerability. It makes finding and fixing holes difficult. Furthermore, giving AI agents access to systems, the internet, or databases creates new attack vectors. Even state-of-the-art agents are vulnerable to prompt injection (Zou et al. 2025). To prevent database deletion 2 or data leaks, human control is essential.

Delegating specialized work to AI without recognizing these risks isn’t just a project failure; it’s a dangerous gamble that saddles an organization with “technical debt” and chronic security risks.

The Bar to Full Automation is High

“AI is still developing. Even if it’s not perfect now, it’ll be solved eventually.”

Many expect AI to autonomously handle high-level tasks like problem definition or analysis design.

But when will that future arrive?

While the difficulty of tasks we demand from AI is rising exponentially, voices questioning the exponential evolution of LLMs are increasing. In my view, it’s very uncertain whether AI’s evolution will fully automate DS work anytime soon.

Automating Multi-Step Tasks is Extremely Difficult

Current LLMs excel at summarization, translation, and code generation. But for complex processes like DS, the error rate amplifies exponentially with each step.

Figure 5: Even if a single task success rate is 95%, the final success rate after 20 steps drops to 36%.

The data analysis process is full of “traps.” LLMs lack the ability to recognize “what’s missing” (Fu et al. 2025) and often try to answer using only available data even when critical context is absent, leading to poor performance (Shen 2025).

Furthermore, while it looks like LLMs perform logical reasoning via “Chain-of-Thought,” evidence suggests they are highly imitating patterns in training data rather than performing true logical reasoning (Zhao et al. 2025).

Has LLM Growth Hit a Plateau? Scaling Laws’ Limits

The progress of AI has been driven by “Scaling Laws”—simply increasing model size and data. But this is hitting physical and economic limits, showing signs of diminishing returns (Coveney and Succi 2025).

A recent AAAI survey showed that the majority of AI researchers believe Scaling Laws alone won’t reach AGI. Even top researchers don’t see AGI on the current trajectory.

LLM Failures Don’t Accumulate as Organizational Knowledge

One might argue:

“Aren’t LLM hallucinations just like human error? Humans make mistakes too.”

But they are different. LLMs don’t know they “don’t know” and lie with confidence. More crucially, LLMs lack the ability to learn from mistakes (similar to anterograde amnesia). Once a session ends, they forget. Even if we try to save memories to files, we hit limits like context window size, recency bias, and context decay.

From a management perspective, “AI fortune-telling” is dangerous because the trial-and-error process is not stored as intellectual property. Human data scientists gain “know-how” for the next project; AI errors are just discarded costs.

Even with Improved AI, Expert Human Intervention is Necessary

Context remains the bottleneck

Even if LLMs understood all statistical theories and implementation, they would still depend on “context.”

As economist Daron Acemoglu notes, tasks that depend on ambiguous success criteria and complex contexts are hard to automate. Data analysis is a classic example. This is reflected in the fact that Copilot user satisfaction is lowest for “data analysis” (Tomlinson et al. 2025).

Real business problems don’t start with clean datasets like Kaggle.

- What is the goal? Who is the audience?

- Is there bias in the data?

- Can we get better data?

- Is the evaluation metric appropriate?

This is tacit knowledge. To maximize AI’s performance, you must verbalize all this and give it as context. But the act of judging which information is useful itself requires high expertise. This is exactly what data scientists do.

Concerns that remain regardless of AI’s evolution

Accountability: Who pays for AI’s failures?

If an AI’s analysis is sloppy and leads to failure, who is responsible? Will businesses bet their fate on a system where accountability is vague?

Arbitrary Use: AI as a tool for “convenient truths”

Data scientists often act as a check on power by presenting objective data. Unlike an independent human with ethics, an AI is much easier to control to produce a desired output by adjusting prompts until the “convenient” answer appears.

The Value of Expertise Won’t Decline

The Compound Interest of Knowledge

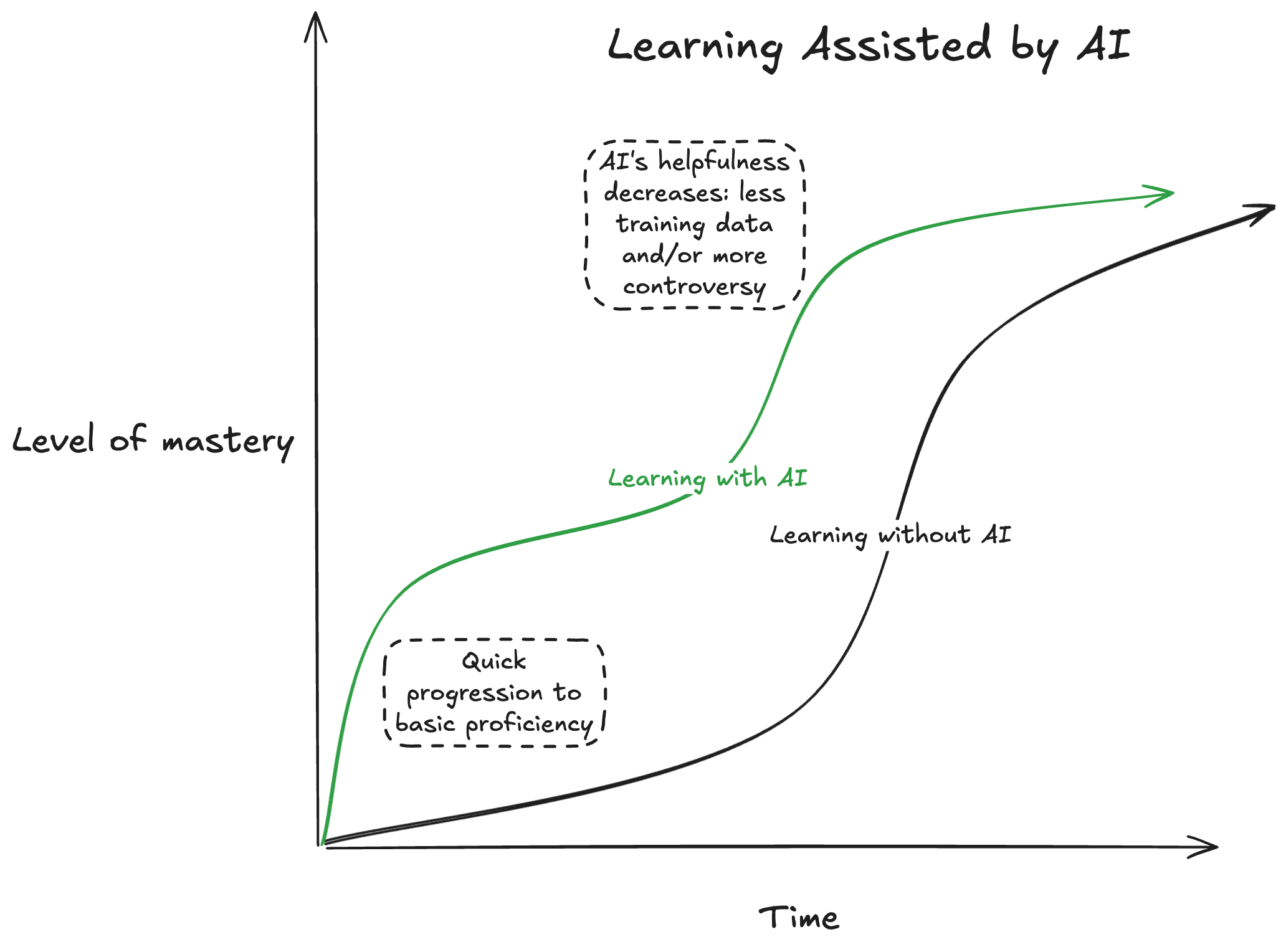

Richard Hamming noted that knowledge and productivity work like compound interest. A foundation of knowledge allows you to deep-dive into new info like a snowball effect.

AI is great for “leaf” (fragmented) knowledge, but the “trunk” (systematic knowledge) cannot be built quickly even with AI. Those with a thick trunk can add leaves much faster. For example, someone who knows Bayesian stats can quickly master tools like Stan or NumPyro using AI. Without the trunk, you won’t even know what to ask the AI.

Figure 6: AI accelerates learning, but reaching a certain level still takes time.

No Need for Junior Levels to be Pessimistic

If a “data scientist” only does simple aggregations, then yes, demand for them will drop. But those jobs should have been automated long ago.

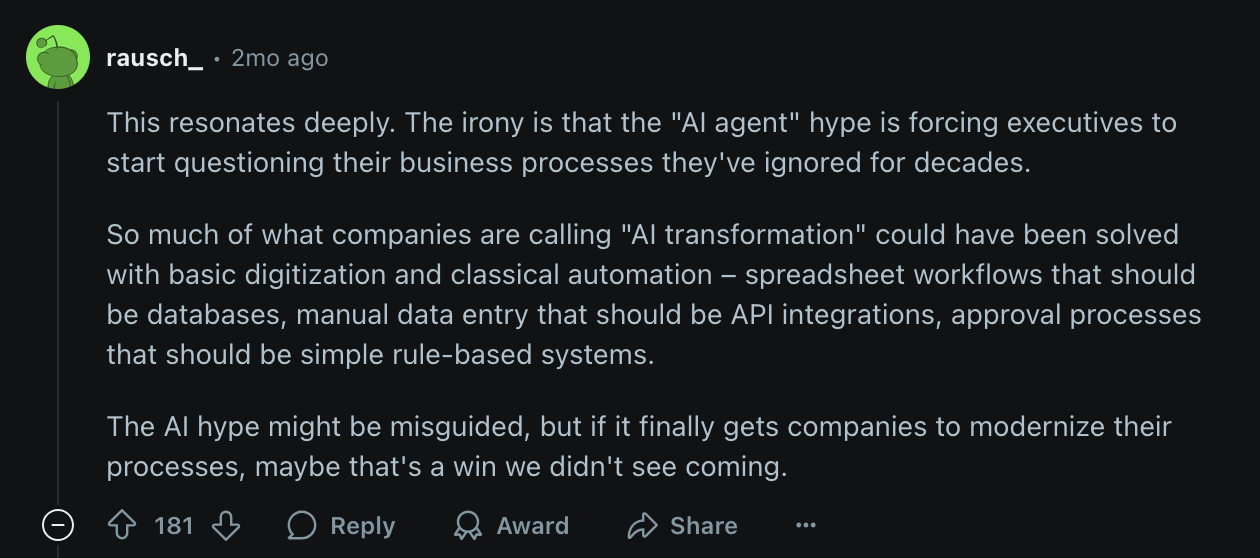

Figure 7: AI agents are finally making management review business processes they ignored for decades.

Much of “AI Transformation” is actually just basic digitization or traditional automation (Software 1.0). Manual worker tasks are zero-sum; automation reduces demand.

Data scientists, however, are knowledge workers. In this realm, the “pie” isn’t fixed. As AI handles parts of the work, new questions and possibilities arise. McKinsey is adopting thousands of AI agents but is valuing human consultants with “distinctive expertise” more than ever.

The comparison “Junior expert vs. Amateur with AI” is nonsense because juniors can also use AI. The “compound interest of knowledge” means even a little systematic knowledge lets you learn faster than an amateur. AWS’s CEO dismissed the idea that AI takes entry-level jobs as “the silliest thing I’ve ever heard.”

Summary: AI is a Tool to Expand Ability, Not an Enemy

I’m not Anti-AI. I’m certain LLMs will bring great changes. I’m warning against the “Silver Bullet” mentality—the idea that “AI will solve everything eventually” makes people turn away from current limits and complexities.

The key is to understand AI’s limits and work with experts to find realistic applications. Steady strategy is needed for AI success.

We should see this as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Just as the power saw didn’t replace carpenters, LLMs won’t replace data scientists. We’ve gained a powerful weapon to tackle more complex, essential problems.

Our strategy should be: Keep learning, and pursue expertise deeply and broadly.

Don’t fear AI; use it as your best partner. This is the future for data scientists.

To those who think data scientists are becoming obsolete:

Don’t worry.

Our job is about to get much more interesting. 3

Extra

Debates about “Data Scientists Becoming Unnecessary” were held in the past too

While researching, I found that similar things were said years ago.

12 years ago

- The day may come when data scientists are no longer needed | IT Leaders

- Maybe we only need 6,000 elite data scientists - TJO’s blog

2 years ago (Actually before ChatGPT)

References

-

There was an incident where an AI deleted a production database and then created fake data and reports to hide the issue. ↩︎

-

I will refrain from mentioning names because it might cause trouble, but in writing this article, I received feedback from trusted friends, seniors, and juniors. I would like to take this opportunity to thank them. ↩︎